This article was originally published on Women’s Media Center’s The FBomb, as part of the Young Feminist Media Fellowship between FRIDA and The Fbomb. This article is written by Ariana Smit, one of the four fellows who was selected as part of the fellowship. A pilot project launched in 2018, it is an attempt to counter dominant narratives that provide little to no space to achievements and accomplishments of young feminist organizers, this fellowship seeks to give an opportunity to young feminist storytellers to themselves tell the story of young feminist trends around them.

“No matter how we shy away from it in Nigeria, LGBT persons are real.”

This is what Owen, a counselor and facilitator for the Initiative for Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights Awareness (ISRHRA), a Nigerian LGBT organization first formed in 2015, recently told The FBomb. His claim that the nation is in denial about the very existence of LGBT people is surprising only in that Nigeria has instituted laws that criminalize and persecute LGBT people, suggesting that the government does believe they exist — and wants to make it impossible for them to live safely and equally in society.

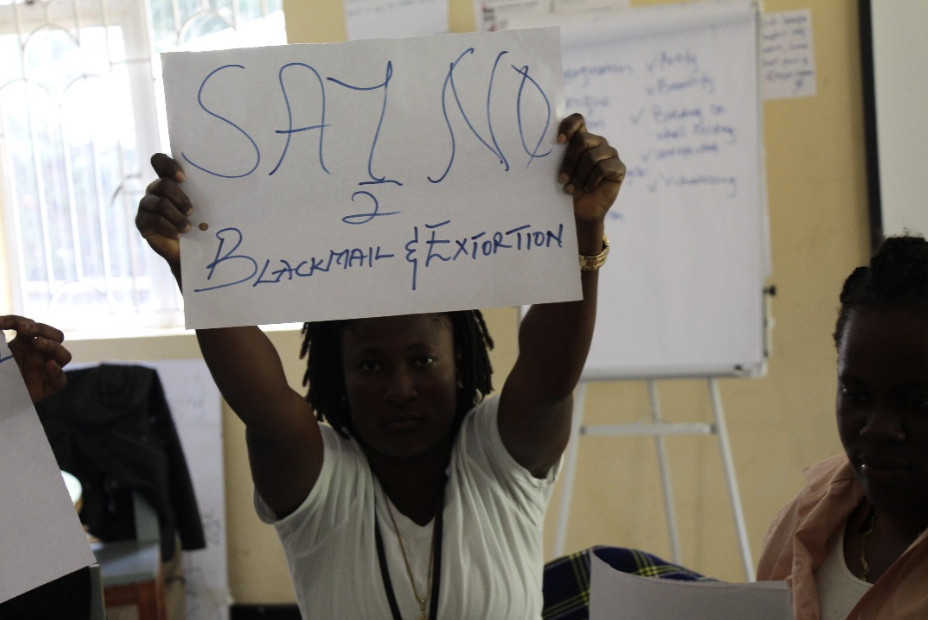

The legacy of LGBT discrimination in Nigeria is long but has become particularly invective in recent years. Consensual same-sex relationships had already been criminalized, but in 2014, President Goodluck Jonathan signed into law the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, which enforced a 14-year prison sentence for gay marriage and a 10-year prison sentence for “membership or encouragement of gay clubs, societies and organisations.” Human Rights Watch states that the new law “officially authorizes abuses against LGBT people, effectively making a bad situation worse.” The law, which not only enforces prison sentences but also legitimizes vigilante and state violence against LGBT people, was spurred on by many cultural and religious beliefs of anti-gay sentiments. This law may have validated and motivated blatant acts of LGBT discrimination. In 2017, for example, police arrested 70 men at an openly gay party in Lagos, with the aim of extorting money from those arrested. In 2018, according to The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERs), a recorded total of 286 LGBT people were violated in ways ranging from blackmail and extortion to sexual violence, arbitrary detention, and violations of due process rights. Mob violence has also become a threat to LGBT people, with groups dragging people from their homes and “cleansing” villages of homosexuality.

Picture credit: ISRHRA

This culture of discrimination is so strong that even progressive leaders in the nation are not immune. Take, for example, the recent backlash aimed at Oby Ezekwesili in response to comments she made at an event about social justice in Nigeria. Ezekwesili, a nominee for the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize and now a candidate for president in the 2019 election, stated that she “absolutely believe[s] in the fact that everyone is entitled to equal opportunity.” Both citizens and politicians interpreted this comment as an endorsement for LGBT rights. Ezekwesili eventually rescinded her remark by emphasizing her religious beliefs, apparently out of the belief that blatantly supporting LGBT Nigerians would leave her politically defunct — such is the state of LGBT rights in Nigeria.

This lack of respect for Nigerian LGBT people, and that population’s inability to access their rights, is why ISRHRA has become a fundamental component in so many LGBT individuals’ support systems. The organization’s mission is “to contribute to the national and regional efforts to promote the human rights of sexual minorities, and to combine regional and national organization together to strengthen their voice.” ISRHRA does this by providing vital psychosocial support and counseling for Nigerian LGBT people after they have faced discrimination in their communities, offering them a safe space to heal, and then helping them reintegrate into society.

Many people who seek help from ISRHRA do so when their sexuality is publicly found out and they are subsequently thrown out of their homes by their families, legally evicted by landlords, excommunicated from their communities, and/or facing extreme violence. The organization provides these at-risk individuals a safe house for a maximum of three months. During this time, residents go through a process of “capacity building,” where they are equipped with various skills to help them get back on their feet again. For example, a typical training session involves local entrepreneurs teaching residents about different business opportunities they can pursue or how to use a computer — even going so far as to impart web design skills. Upon returning to their families after their three months at the ISRHRA safe house, many former residents have reported that the new skills they learned gave them financial stability. They say this stability, in turn, makes them more accepted in their communities because it contradicts the common belief that people of an LGBT identity cannot amount to anything. Owen concurs that financial independence significantly benefits people after they have experienced forms of discrimination like being kicked out of their homes or being fired from their jobs.

Another form of capacity building that ISRHRA facilitates is teaching LGBT people about their rights. Specifically, ISRHRA has found that few Nigerians are aware that anti-LGBT laws, such as the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, actually contradict the Nigerian constitution, which clearly states that “the state social order is founded on ideals of freedom, equality, and justice” and that “every citizen shall have equality of rights, obligations, and opportunities before the law.” ISRHRA also partners with other Nigerian organizations that provide legal support for LGBT people who come into conflict with the government. By doing this, ISRHRA makes sure that every LGBT person who walks through their doors is met with as much assistance as they can provide.

ISRHRA’s capacity-building strategy is meant not only to help LGBT people resurface after experiencing discrimination but also to help them teach their communities about LGBT rights. ISRHRA coordinates advocacy visits in partnership with allied organizations that focus on human rights in rural communities. These visits teach community members about LGBT people’s lived experiences and question religious and traditional institutions that are responsible for spreading wrong beliefs about being LGBT. For example, it is a common belief in some communities that people can be “cured” of their homosexuality through deliverance — in other words, that praying to God may “cast out” a person’s homosexuality. Dispelling myths like these not only helps shift common perceptions about how LGBT people should be treated but also allows LGBT people to feel more comfortable seeking help locally. This creates a necessary circle of advocacy, in which ISRHRA makes it possible for people in Nigeria to take charge of their own thoughts and opinions about LGBT rights.

ISRHRA is constantly looking for new ways to grow awareness about LGBT rights. Currently, they are developing the Football Project, which focuses on bringing LGBT people and the community together through sport, something Owen asserts is a means of teaching and therapy for LGBT individuals in an LGBT-hostile society. So far, the Football Project has conducted a few competitions and has seen incredible results. As Owen states, “Sports is a game of love,” as it unites people across different identities, and ISRHRA’s goal with this is to bring together LGBT people and other members of the community.

Despite what many Nigerians believe, LGBT persons are real. Organizations like ISRHRA are working tirelessly to generate unique opportunities for them to get back on their feet again and create change in their communities. Of course, as valuable as this community work is, there’s still a long way to go before the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act is repealed and LGBT people are fully integrated into Nigerian society in meaningful and tangible ways. But ISRHRA is helping LGBT people take their first steps toward that reality.

By Ariana Smit