Berta Cáceres’ assassination reminds us of the systemic violence targeting women who dare to challenge patriarchy and capitalism. Ayesha Constable writes.

On March 3, Berta Cáceres, Honduran environmental activist and indigenous leader of the Lenca people, and co-founder and coordinator of the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras, was killed by masked men who broke into her home. Her killing has sparked international outcry from environmentalists, human rights activists and ecofeminist groups who are calling for an end to savage the attacks on activists. The most recent tragedy has also brought into sharp focus the global nature of the crisis regarding the violence targeting environmentalists. The matter has become a human rights issue and the Human Rights Watch World Report of 2013 explained that activists vocal in opposing mining and energy operations that they say threaten the environment and will displace tribal communities from their land continued to face attack in 2012.

International watchdog group Global Witness in its 2013 report Deadly Environments named Honduras as the second deadliest country in the world for environmentalists. Between 2010 and 2014, 101 activists were murdered in Honduras, the highest rate per capita of any country surveyed in a report by Global Witness, earning it the ‘deadliest place for environmentalists’ title in 2014. Global Witness figures, released following Berta’s killing, show that at least 109 people were killed in Honduras between 2010 and 2015, for taking a stand against destructive dam, mining, logging and agriculture projects.

A protest rally in memory of Berta

Since the 2009 coup, Honduras has witnessed an explosive growth in environmentally destructive megaprojects that would displace indigenous communities. Almost 30 per cent of the country’s land was earmarked for mining concessions, creating a demand for cheap energy to power future mining operations. To meet this need, the government approved hundreds of dam projects around the country, privatizing rivers, land, and uprooting communities. As far back as 2014, Oliver Courtney, senior campaigner at Global Witness described the rising activist deaths “as a symptom of our global environmental crisis.”

Women are increasingly the targets of these attacks. According to the Urgent Action Fund for Women’s Human Rights, 12 female environmental leaders were killed in Latin America alone by 2014. The issue has garnered increased interest among civil society groups as well as academics with McKinney and Fulkerson (2015) arguing that women and the environment represent twin dimensions of exploitation that suffer from the current capitalist regime and patriarchal structures of domination therein.

Berta Cáceres rallied the indigenous Lenca people of Honduras and waged a grassroots campaign that successfully pressured the world’s largest dam builder to pull out of the Agua Zarca Dam. They argued that the dam would cut off the supply of water, food and medicine for hundreds of Lenca people and violate their right to sustainably manage and live off their land. In 2014 Berta told BBC reporters that she had received numerous death threats because of her opposition to a dam that would force her community off their ancestral land. She claimed she has been forced to live a “fugitive existence”

Members of FRIDA community and beyond join the #JusticeforBerta rally in New York City

In 2015, she was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize – a prestigious award recognizing grassroots environmental activists from around the world. Former winners of the prize, in a joint statement issued following her killing, lamented the constant threats with which Berta lived. Former winners of the prize have stated that: “Berta was surrounded by threats and bullets, and at times, cars waiting for her in the road with armed men. But she continued to fight for human rights and the environment–women violated by their partners, children with malnutrition, and of course, the problems many of us worked on with her, unsustainable mining and hydroelectric dams.”

Billy Kyte, a campaigner at Global Witness had lamented in 2015, “In Honduras and across the world, environmental defenders are being shot dead in broad daylight, kidnapped, threatened, or tried as terrorists for standing in the way of so-called ‘development’.” In 2014 Global Witness said it is calling on governments “to monitor, investigate and punish these crimes, and for Honduras to address abuses in the upcoming review of its human rights record at the UN Human Rights Council”. And despite those calls, Berta was murdered.

Grahame Russell of Rights Action claims that Berta was killed by corporations and investors who conceive of the world – its forests and earth, its natural resources, its rivers, waters and air, its people and all life forms – as exploitable and discardable objects, and then steal, kill and destroy mightily to make their millions and billions. The politics and economics of the situation is rooted firmly in capitalism and patriarchy and as such women and other vulnerable groups will continue to suffer.

In 2014, Cáceres told Thomson Reuters Foundation that “as women we are exposed to violence from businesses, governments and repressive institutions – but also to patriarchal violence. It is three times worse for an indigenous woman. The media criminalises us too. They try to take away our credibility, (they) say we’re armed groups, that we attack private investments, which we don’t exist, we’re from dysfunctional families, we’re bitches and corrupt.” She told Grist that the level of aggression with which she had been met was greater because “We are women who are reclaiming our right to the sovereignty of our bodies and thoughts and political beliefs, to our cultural and spiritual rights — of course the aggression is much greater.”

The Women’s Earth & Climate Action Network posit that indigenous women and women from low-income communities and developing countries bear a heavier burden from the impacts of environmental changes such as climate change because they are more reliant upon natural resources for their survival and/or live in areas that have poor infrastructure, which makes their communities particularly vulnerable. Female activists have argued that they have less support than those working on women’s rights in general, such as sexual and reproductive rights.

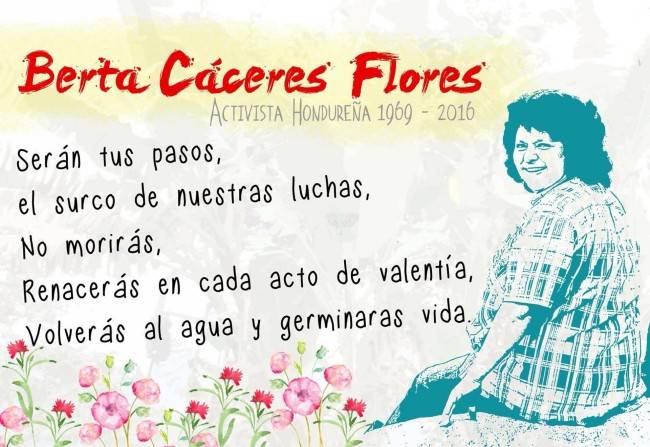

‘Your steps will be the furrow of our struggles.

You won’t die but live on in every act of courage.

You will come back as water, and germinate life.’

Berta was a mother, a sister, a daughter. She was selfless in her determination to defend the rights of her people and the land that was of significant cultural and spiritual value. Many are calling for an independent investigation through the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Beyond that there remains a lot of work to do to stem the tide of attack on activists. Activists are relying on the international community to lobby their governments against supporting projects like that for which Berta was killed.

Jagoda Munic, chairperson of Friends of the Earth International (FoEI) affirm there is no environmental justice without an end to all forms of violence against women and to the exploitation of women’s reproductive and productive work. We cannot remain silent as men and women are killed for trying to protect the air, water and land on which their lives depend. We cannot sit idly by and wait for the next person to take action. We each have a role to play because ultimately ‘we each are the leaders we have been waiting on’.

In 2014 Cáceres voiced her commitment to the process, her commitment to staying and defending the land- “I want to live and enjoy my life but I can’t do it because I feel the responsibility that this is a collective process and collective responsibility”. She paid the ultimate price for her commitment to her people and their land- her life.

Ayesha Constable is one of FRIDA’s advisors from the Latin American and the Caribbean region. Read more about our LAC advisors here.

Click here to read FRIDA’s statement on the assassination of Berta Cáceres and click here to read more statements and calls to action.