This is the translated and edited version of a conversation between Ledys Sanjuan and Majandra Rodriguez, facilitated by Maria Alejandra Escalante. Originally recorded as a sound byte in Spanish (releasing soon!), here are some excerpts to a truly enriching discussion:

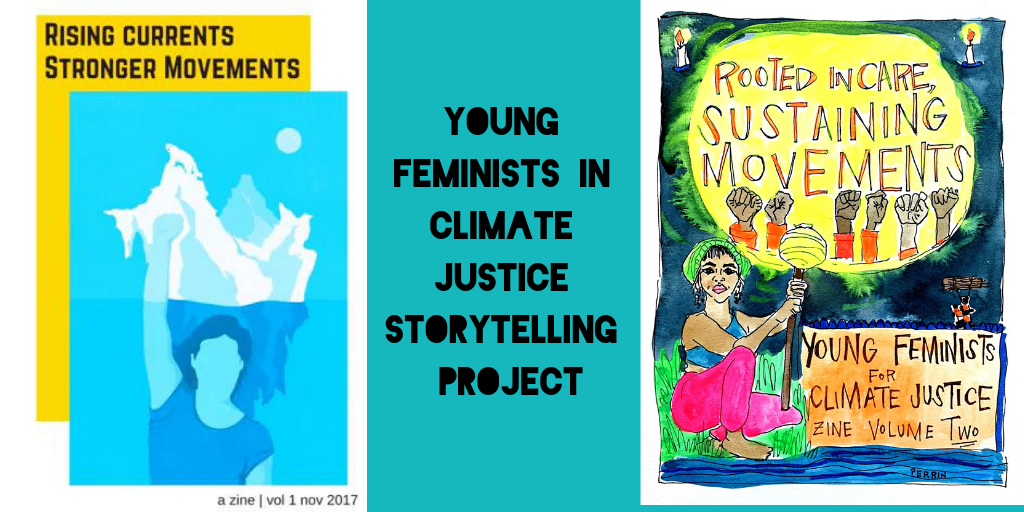

Majandra is based in Lima, Peru where she co-coordinates the national youth network TierrActiva Peru and is involved in feminist and climate/environmentalist activism in different spaces. Ledys is based in Bogotá, Colombia, and currently works as Senior Advocacy Officer for FRIDA The Young Feminist Fund. Maria Alejandra is a Colombian queer and young feminist activist, part of the youth collective TierrActiva Colombia, interested in deepening the conversation around intersectionality and is the Climate Justice Consultant at FRIDA. The three of us have been involved in the creation, curation, and coordination of the Young Feminist for Climate Justice Storytelling Project. This conversation reflects upon the themes of this project, and the intersectional, eco-feminist, and young feminist organizing, particularly in Latin America.Maria Alejandra (M): Let us start from the beginning! What is the story of this project and what brought us to be thinking about self and collective care for activists?

Ledys (L): The need to speak about care is important because it is a missing or is weak conversation in the climate justice movement, and is something that young feminists are practicing. We have a need of centering self and collective care for the movement—to talk about burnout, fatigue, how activists are working too much and that does not let us move forward as a movement. This perspective comes from personal experiences of burnout and normalizing it as a semi-permanent state. There was a moment in which I was exhausted for a long time. It was hard to heal and come back to life, to want to get involved in activism once again. I learned in the process and met many women who were going through the same. We realized how important it is to talk about care, and the need to stop, pause, spend time with families, care for our bodies.

Majandra (Ma): I became involved in climate activism when I was 19 years old. 2009 was an important year in Peru, marked by a series of protests and violent confrontations between indigenous communities and the police/central government in the northern amazonian region over the sellout and appropriation of ancestral indigenous territories. It was shocking to witness this violence, particularly of indigenous women crying for their husbands, children, and dead or wounded peers. Also, as a young woman in Peru, a place with some of the highest rates of femicides in Latin America, I have come to identify and been identified as a woman in a sexist society. These struggles and contexts are not isolated; I am not a woman one day and an environmentalist activist the other. These are all parts of our identities. It was easier for me to become active in environmental struggles than to recognize myself as a feminist, because I rejected my perceived identity as a woman for years. It was painful to engage with issues of gender. It was not until a few years ago that I began truly processing how feminism and gender oppression can be a part of my political struggle.

M: I see the Young Feminists for Climate Justice Storytelling Project as a platform to make our experiences visible, and to let us see that we are not alone in our resistance. This means that we have tried to build a space, a voice, and different perspectives about feminism in a context of environmental crisis. Let us reflect on why these spaces are necessary for young and diverse feminists.

L: Through this project, we are recovering what young feminists, especially in the Global South, who work on environmental issues are doing: re-living practices to connect with the earth and our ancestry. This was either not visible or not legitimized as activism. In many spaces in the climate justice movement, largely dominated by men, protests, meetings, lobbying, petitions are things that get prioritized. This project wants to connect the struggle for our territories with these practices of care and healing that all of us as activists should be able to access.

M: It is also a way of re-conceptualizing what activism means. In many ways, activism has been framed by and from a Northern Anglo-Saxon perspective while people who are defending their territories in countries in the Global South may not be perceived of as activists. In some ways, this project is about reconceptualizing how we see ourselves – we are as defenders of life. We chose the theme of self and collective care in the digital and physical space for this edition. This means we are also talking about how technology and its rapid development lends us tools that can be used in our advantage, but often also generates disadvantages. The use of technology is impacting our intersectional movements in so many ways.

L: For young feminists, technology helps us connect beyond borders. It also exposes activists, particularly those defending our territories, to threats, massive surveillance, physical and online harassment. With FRIDA, we have been working hard on building tools and knowledge for young feminists because they are also confronting states and multinational corporations that can use more advanced technology to attack and harass activists. This also has tough physiological impacts on people who develop traumas and carry a lot of pain. In workshops that we have organized with FRIDA and Mama Cash around this topic, we have talked with activists about how their bodies are doing, if they were in touch with their families. All of this is crucial when we talk about security and wellbeing.

Ma: One of the biggest challenges for the Young Feminists for Climate Justice network is our virtual and remote connection. This not only implies lots of logistical details, but also means that English becomes our main language. In my context, this is an obstacle for those who do not have the privilege and opportunity to learn this language. In rural areas, even if you have a smartphone, it is still pretty challenging to connect to an online call, webinar, or social media. Speaking of self-care, virtual spaces and remote organising can also feel isolating, which is why being able to meet, hug, look and listen to each other is so important. And these physical meetups must be thought beyond the idea of “let’s all fly to this or that conference or event” which require lots of resources. As a global network, it is important not to forget the local bases and connect to those immediately around us. So the question becomes how to keep building an intersectional movement taking into account the differences and inequalities in social classes, between urban and rural communities.

M: The use of technology also influences how we understand the collective and where the centers of the social movements are located. The last experts report for the UN on climate science has been produced thanks to an increasing improvement of technology that allows us to interpret the causes and effects of climate change, making this environmental crisis ever more clear and palpable. The real question is: how is this science reaching our movements?

Ma: The most active people in our environmental movements are needing and seeking knowledge to understand how this is happening and what we are confronting, and they find this in social media, universities, friends. Personally, this IPCC report has affected me hugely because it lays out clear and harsh information: we have 12 years, until 2030, to cut down our current emissions by 50%….just think about what this really implies. With the current national commitments to lower emissions, we are looking, at least, at a 3°C increase of global temperature. The Paris Agreement seeks to limit the increase to 2°C, with maximum efforts of reaching only 1.5°C. This 0.5°C difference means much more than what was initially calculated by climate science. We are talking about more than 10 million displaced people due to sea level rise, more people driven to extreme poverty because of climate change, and what this means for agricultural production, natural disasters, livelihoods. I’m still processing all of this. Talking to people, many of us ask what can and must we do.

M: Speaking about a potential 3°C warmer world and the impacts of this scenario, it is no surprise that facing the future can bring fear, disillusion, and fatigue and question if we are doing the right thing or enough. How can we stay and strengthen this intersectional movement as activists and feminists, taking into account these feelings? What can re-charge us to continue this work?

L: It is important that people understand that while there is this pressure around climate change, we also need to heal our own relationship to earth, our bodies and beings. I get re-energized through these feminist gatherings, mainly in Latin America, where we can connect our struggles and live that intersectionality. The use of artivism in these spaces is powerful and we could use that better in the climate movement. Within feminist discussions, environmental issues often feel like a specialized topic. How can we use the language of care to make these connections? When there is a group of people around you who practice honesty and love and accept you, you can transcend many of the fragmentations of our activism, like the relationships among feminists. How can we create connections among activists based on respect and love?

Ma: it is important to heal our relations with ourselves, among each other, with earth and our bodies. I believe that understanding the root of the reason of our activism means healthier decisions. Sometimes, that means that we should not go to a protest or a meeting, but rest and be with family and friends. It also means understanding that in order to take care of the people I love, I should continue fighting. That is the balance. The idea is to be able to keep doing this in the long term, not necessarily as a means to an end, but as a process in itself. When we talk about systemic change, we mean that the economic, political, and cultural systems are not working; we must re-center care, love and love for life. This already implies a deep change in oneself, as we are all part of these systems. What keeps me motivated is the community, the collective, compañerxs (peers) who we work alongside as family. This means I am not alone.

Ma: it is important to heal our relations with ourselves, among each other, with earth and our bodies. I believe that understanding the root of the reason of our activism means healthier decisions. Sometimes, that means that we should not go to a protest or a meeting, but rest and be with family and friends. It also means understanding that in order to take care of the people I love, I should continue fighting. That is the balance. The idea is to be able to keep doing this in the long term, not necessarily as a means to an end, but as a process in itself. When we talk about systemic change, we mean that the economic, political, and cultural systems are not working; we must re-center care, love and love for life. This already implies a deep change in oneself, as we are all part of these systems. What keeps me motivated is the community, the collective, compañerxs (peers) who we work alongside as family. This means I am not alone.

M: But is there such a thing like an intersectional movement? And if so, where are we, where is our power and agency, and what do we still need to learn to keep building change?

Ma: The movement is increasingly becoming [intersectional]. Maybe the use of the term “intersectionality” is used more widely in a US context. In other contexts, not everyone calls themselves a feminist even when the principles of our work embody those struggles. In Peru, I have been part of spaces that look at the historical memory of the internal armed conflict we went through, and this means we talk about torture, missing bodies, and violence towards Quechua speaking women. We talk about corruption, legislation, government elections, and I have seen trans* peers explaining how that space of memory is also part of their history, as this persecution and discrimination was also transphobic and homophobic. More and more I see examples like these and I see a generational change involved here. When we see the old leftist parties and the more traditional progressive and social struggle, we see that they are sexist and homophobic. Now I see many young people saying that our sexuality and gender are relevant in these discussions, and that if these spaces do not represent us, then we seek to change them or we create new spaces. It is a fight against the mainstream in our movements and the conservative spaces with power, history, and tradition.

L: It is also important to recognize other spaces of struggle that are not seen as such, like our own minds. Or for example, many of us have been socialized as women, and we have troubles legitimizing our activism—sometimes this begins with a voice within ourselves, and sometimes it is the echo of our society. This is what intersectionality is about here: connecting our bodies to what is happening to our earth, and learn that we cannot fight against each other or without the other. When we talk about our bodies being made into feminized or racialized spaces, we start seeing the power dynamics within the system. This project aims to let us see that we, young feminists, are not just trying to stop climate change or reach an enormous goal, but we are saying what impacts us, and we are offering practices as well as stories of fatigue and healing. We should not feel as if we needed to change everything by ourselves alone, and yet, we should give each other the space to try new strategies.